Ligament and tendon sprains account for almost half of all injuries in youth sport and can keep athletes off the field and ice for months at a time. Injuries of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), a major ligament which runs diagonally in the middle of the knee, are particularly devastating, often occurring when an athlete – typically in sports like soccer, football or basketball – suddenly decelerates and pivots at the same time.

Yet despite the statistics, research on ligaments and tendons is limited because, unlike blood or muscle, tissue samples that can be examined are difficult to obtain, says Daniel West, who is doing an industry related post-doctoral fellowship in the Iovate/Muscletech Metabolism & Sports Science Lab, run by Assistant Professor Daniel Moore at the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education

“You can study the metabolism of ligament cells (fibroblasts), how they grow and multiply, flat on a dish. However, that doesn't tell you any functional information, such as how strong or elastic they are,” says West. Fortunately, there is a technique, used in only a handful of labs around the world, that lets scientists form mini 3D ligaments that can be tested for metabolism and strength.

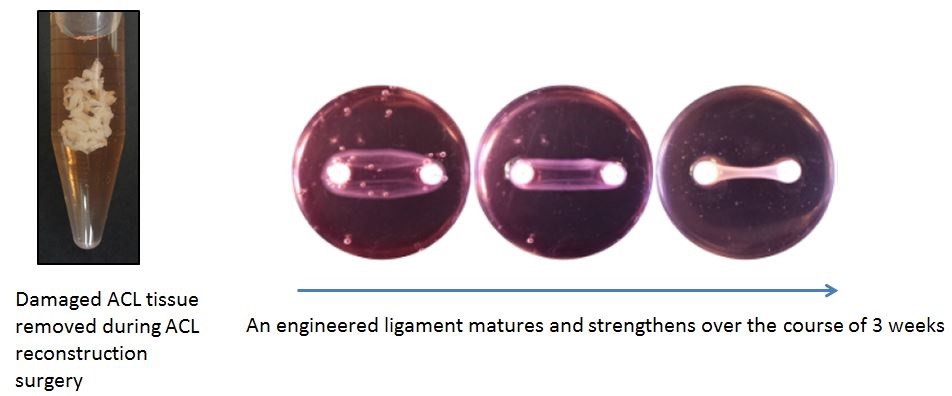

“ACL injuries generally require surgery. During surgery, the injured ligament is cut out and normally discarded. Instead of discarding it, we take the ligament at the time of surgery, harvest the alive cells from it, and re-grow a mini ligament that can be used for research,” says West. “These immature ligaments are smaller and weaker than healthy ligaments and so aren't good for transplanting back into the people, although some testing of this is underway. However, they are an excellent research model to help us understand the underlying factors that make ligaments strong and healthy.”

West learned the technique while doing his first post-doctoral fellowship with Professor Keith Baar at UC Davis. A video featuring West and his colleagues demonstrating the technique was recently posted on JoVE, a scientific video journal that publishes how-to videos of scientific experiments from top laboratories around the globe.

When the opportunity to work at KPE with Professor Moore presented itself, West was happy to take it. He and Moore knew each other from ten years ago, having shared the same PhD supervisor Professor Stuart Phillips at McMaster University.

“At one point I actually said to Dan when we were going to go our separate ways, I’m going to learn some new things and then I’ll come back and work in your lab,” says West.

Now that he is, the hope is to merge some of the fundamental science techniques, such as the “recycling” of discarded ligaments, with the human physiology research that is the focus in Professor Moore’s lab.

“In Dr. Moore's lab we are interested in partnering with Toronto orthopaedic surgeons and the David Macintosh Sports Medicine clinic to use this model to reveal how exercise and nutrition interventions can help repair injured ligaments, or prevent those injuries from happening in the first place.”

Professor Moore calls it a unique opportunity to apply a more holistic rehabilitation strategy to injured athletes.

“Our current research is focused on skeletal muscle repair and growth,” he says. “Injured athletes or those recovering from reconstructive surgery generally lose a significant amount of muscle mass that subsequently must be recovered during their rehabilitation. This research model will give us the ability to study how exercise and nutrition can help rebuild and strengthen both skeletal muscle and the connective tissue in tendons and ligaments, ultimately accelerating the athlete’s return to play.”

For more information, please contact:

Daniel West, PhD

Postdoctoral fellow

KPE

daniel.west@utoronto.ca

Dan Moore, PhD

Asst Prof.

KPE

dr.moore@utoronto.ca